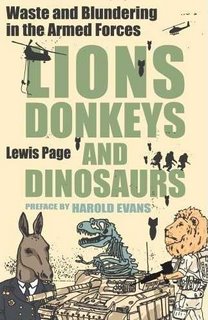

Lewis Page, the man who brought us the book Lions, Donkeys and Dinosaurs - tabulating some of the MoD's procurement scandals – has done it again.

Lewis Page, the man who brought us the book Lions, Donkeys and Dinosaurs - tabulating some of the MoD's procurement scandals – has done it again.For the ERC, (Economic Research Council), he has produced a paper entitled "Cost-Effective Defence". It details how, in his view, the UK could radically reorganise its Armed Forces within the existing budget to finally move them beyond their redundant Cold War footing.

He explains in detail what equipment and capabilities needs to be bought and discarded and how funds can be found for a fifty percent pay rise for combat troops. He believes that the correct level of pay for a private is about £22,000 - which is still less than a policeman or firefighter. This, he writes, "can be paid for within the existing budget by cutting back on the Eurofighter and other pointless procurement projects whilst still retaining funds to buy the equipment and capabilities our armed forces actually need."

The ERC, which claims to be Britain's oldest economics-based think-tank, founded in 1943, is to be commended for publishing the work. There is little enough being done to provoke a debate about the nature and structure of our armed forces and, if it encourages a few pieces in the media, that could be helpful.

The ERC, which claims to be Britain's oldest economics-based think-tank, founded in 1943, is to be commended for publishing the work. There is little enough being done to provoke a debate about the nature and structure of our armed forces and, if it encourages a few pieces in the media, that could be helpful.What is particularly useful is Page's initial analysis of the central defects of our defence effort. The problem is that our armed forces are likely to face three types of opposing forces: what he calls "paramilitaries" (i.e., insurgents); the armed forces of minor powers; and the armed forces of nuclear powers. The last is extremely unlikely, the second happens every ten years and the first continuously since 1945. But, he notes, the UK's military capabilities reflect the reverse of these facts.

Page thus argues that insufficient effort is being made in the provision of deployable ground combat troops with a small logistical footprint, utility and transport helicopters, both heavy and light military air transports, sea-based aviation of every type and "recruitment and retention of suitable junior servicemen and women."

But, he declares, giving the MoD more money would be unwise and merely continue present duplication of effort and "overextension into foolish areas" to persist. A radical reorientation of existing resources is required first.

We would, as you can imagine, completely endorse Page's view on this. More cash to the MoD as presently constituted would simply be throwing more money after bad. And Page offers plenty of detail as to where the axe would fall – not least on the Eurofighter Tranche 3 (the ground attack version), the Nimrod MR4 maritime patrol project, a halt to the Type 45 building after six ships (which will probably happen anyway) and reducing the Royal Navy frigate and destroyer fleet to 14 ships.

We would, as you can imagine, completely endorse Page's view on this. More cash to the MoD as presently constituted would simply be throwing more money after bad. And Page offers plenty of detail as to where the axe would fall – not least on the Eurofighter Tranche 3 (the ground attack version), the Nimrod MR4 maritime patrol project, a halt to the Type 45 building after six ships (which will probably happen anyway) and reducing the Royal Navy frigate and destroyer fleet to 14 ships. In fact, reflecting his previous experience as a Royal Navy officer, Page is savage on grey floating "toys", although he wants more amphibious warfare ships and the two carriers (preferably reconfigured for conventional take-off and landing). Overall, he thinks he can save £20-25 billion from the proposed procurement budget, all of which he would use to improve pay and conditions, with a starting salary for privates and equivalents to be at least £22,000, especially for combat troops.

In fact, reflecting his previous experience as a Royal Navy officer, Page is savage on grey floating "toys", although he wants more amphibious warfare ships and the two carriers (preferably reconfigured for conventional take-off and landing). Overall, he thinks he can save £20-25 billion from the proposed procurement budget, all of which he would use to improve pay and conditions, with a starting salary for privates and equivalents to be at least £22,000, especially for combat troops.We do not entirely agree with his emphasis on paying privates more and, if anything, it seems that within the services, this is not the main issue. Furthermore, with the current overseas bonus, it must be even less of an issue than it was.

This though is not the only area where Page's arguments start to unravel. When it comes to green "toys", he is clearly out of his depth. That is not to say that a former naval person cannot acquire considerable expertise in army equipment and land warfare, but you have to put the work in – which Page does not seem to have done. Little things, as well as big, betray him. In the former category, he seems to be unaware that the Saxon APC has been junked and that the Phoenix UAV has been withdrawn from service.

This though is not the only area where Page's arguments start to unravel. When it comes to green "toys", he is clearly out of his depth. That is not to say that a former naval person cannot acquire considerable expertise in army equipment and land warfare, but you have to put the work in – which Page does not seem to have done. Little things, as well as big, betray him. In the former category, he seems to be unaware that the Saxon APC has been junked and that the Phoenix UAV has been withdrawn from service.Page's biggest problem though is in dealing with the issue which we promised we would address in an earlier piece - the vitally important issue of how, in counterinsurgency operations, you bring the battle to the enemy.

Here – as in all military procurement – one should not be defining the equipment so much as the tasks, and then designing the equipment to allow your people to carry them out. In that earlier piece we already set out the need to protect your own personnel. In the context of the IED having become the insurgents' main weapon, from that has evolved a range of mine/blast protected vehicles, the design principles of which are very different from those of "conventional" armoured vehicles.

Here – as in all military procurement – one should not be defining the equipment so much as the tasks, and then designing the equipment to allow your people to carry them out. In that earlier piece we already set out the need to protect your own personnel. In the context of the IED having become the insurgents' main weapon, from that has evolved a range of mine/blast protected vehicles, the design principles of which are very different from those of "conventional" armoured vehicles. This is Page's first error, in that he fails completely to recognise the need for these, the need for patrol vehicles that give better protection than the "Snatch" Land Rovers and other lightly armoured vehicles.

This is Page's first error, in that he fails completely to recognise the need for these, the need for patrol vehicles that give better protection than the "Snatch" Land Rovers and other lightly armoured vehicles.His second error – one which the Army also makes – is failing to realise that dealing with IEDs must be carried out on a proactive as well as reactive basis. The Americans – for all their other mistakes – have understood this, with the formation of their IED-hunting teams and their requirement for specialist equipment.

Interestingly, the NAO Report points out that shortfalls in recruitment/retention are patchy and one of the key shortages is in bomb disposal officers – an area where the British Army is singularly badly equipped.

However, if protecting your own people through passive and active defences formed the first unbreakable principle - the need to minimise "unnecessary" deaths - the second rests on the need to make a "promise" to the insurgents. The first says, effectively, if you try to kill us you will fail; the second says, if you try, you will die.

The reality of an insurgency though is that the enemy is invisible until he reveals himself and is identifiable only for so long as he engages – merging back into the environment to become invisible again. To the question, "how do you kill an insurgent?" therefore, the answer is "very quickly" - or not at all. Most often, you have a fleeting "target of opportunity" and your equipment must be geared to maximising the chances of a "kill" in time afforded.

The reality of an insurgency though is that the enemy is invisible until he reveals himself and is identifiable only for so long as he engages – merging back into the environment to become invisible again. To the question, "how do you kill an insurgent?" therefore, the answer is "very quickly" - or not at all. Most often, you have a fleeting "target of opportunity" and your equipment must be geared to maximising the chances of a "kill" in time afforded.Some of this is old technology – intelligence-led ambushes and the use of long-range, pre-positioned snipers who take out the enemy when he appears. But where, for instance, you get the hit-and-run mortar team, new technology is vital. We have already spelt this out in terms of needing accurate counter battery radar, UAVs to carry out routine surveillance, plus light helicopters that can carry out surveillance functions, which can mount attacks and which can deliver rapid response ground teams.

But what are also proving extremely valuable are Unmanned Aerial Combat Vehicles (UCAVs). The later models such as the Predator B – now renamed the Reaper – are able to deliver a variety of munitions including laser/GPS guided bombs, and up to 14 Hellfire anti-vehicle/personnel guided missiles. With their advanced surveillance capabilities, these, above all, seem to hold out the most promise of being able to deliver an instant and deadly response to the fleeting insurgent. We have already seen many examples of their utility.

But what are also proving extremely valuable are Unmanned Aerial Combat Vehicles (UCAVs). The later models such as the Predator B – now renamed the Reaper – are able to deliver a variety of munitions including laser/GPS guided bombs, and up to 14 Hellfire anti-vehicle/personnel guided missiles. With their advanced surveillance capabilities, these, above all, seem to hold out the most promise of being able to deliver an instant and deadly response to the fleeting insurgent. We have already seen many examples of their utility.But here, as with the other equipment issues, Page does not seem to be on the same planet. He makes no provision for re-equipping the Army with blast protected vehicles or supplying it with large numbers of light attack/reconnaissance helicopters. Furthermore, he costs only for the Watchkeeper in his UAV programme, with no provision for UCAVs. Yet these essential additions would absorb a considerable portion of his expected savings and that is without even considering the extremely expensive enhancements in satellite communications capabilities needed to operate an extensive number of UAVs.

In this 40-page paper, though, you would expect that there are many other ideas, and indeed there are. Another major suggestion from Page is the total abolition of tank regiments, which he argues should re-role as armoured infantry, switching from Challengers to Warriors, while the existing mechanised infantry would convert to light infantry.

Yet this ignores completely the experience of an increasing number of armies, from the Americans to the Israelis – and now the Canadians, all of whom are reconsidering the role of heavy armour in counterinsurgency operations. The Israelis are even considering moving away from lightly armoured personnel carriers to the heavy Namera APCs, based on the Merkava MBT.

Yet this ignores completely the experience of an increasing number of armies, from the Americans to the Israelis – and now the Canadians, all of whom are reconsidering the role of heavy armour in counterinsurgency operations. The Israelis are even considering moving away from lightly armoured personnel carriers to the heavy Namera APCs, based on the Merkava MBT.Strangely though, where there is room for significant financial savings – such as in abandoning the FRES programme – which Page clearly does not understand – he comes up with no recommendations. And, despite the extraordinary cost of the Future Lynx programme, this is allowed to stand.

All of this makes for an extraordinarily shallow paper, which offers very little* that can be treated as a serious contribution to defence strategy. Nevertheless, up front, I did commend the Economic Research Council for publishing the paper – as a contribution to the debate - and stand by that. I wish, though, the Council had been a little more aggressive in testing the arguments of its author before going public.

* Originally, I wrote "nothing" but, on reflection, that is a little too severe. There are some good ideas in the paper, albeit very few.

COMMENT THREAD